Angular Wagtail and Wagtail Single Page App Integration are officially 1.0 and stable. It’s time for a more complete getting started guide. Let’s build a new app together. Our goal will be to make a multi-site enabled Wagtail CMS with a separate Angular front-end. When done, we’ll be set up for features such as

- Map Angular components to Wagtail page types to build any website tree we want from the CMS

- All the typical wagtail features we expect, drafts, redirects, etc. No compromises.

- SEO best practices including server side rendering with Angular Universal, canonical urls, and meta tags.

- Correct status codes for redirects and 404 not found

- Lazy loaded modules

- High performance, cache friendly, small JS bundle size (In my experience 100kb – 270kb gzipped for large scale apps)

- Absolutely no jank. None. When a page loads we get the full page. Nothing “pops in” unless we want it to. No needless dom redraws that you may see with some single page apps.

- Scalable – add more sites, add translations, keep just one “headless” Wagtail instance to manage it all.

Start with a Wagtail project that has wagtail-spa-integration added. For demonstration purposes, I will use the sandbox project in wagtail-spa-integration with Docker. Feel free to use your own Wagtail app instead.

- git clone https://gitlab.com/thelabnyc/wagtail-spa-integration.git

- Install docker and docker-compose

- docker-compose up

- docker-compose run –rm web ./manage.py migrate

- docker-compose run –rm web ./manage.py createsuperuser

- Go to http://localhost:8000/admin/ and log in.

Set up Wagtail Sites. We will make 1 root page and multiple homepages representing each site.

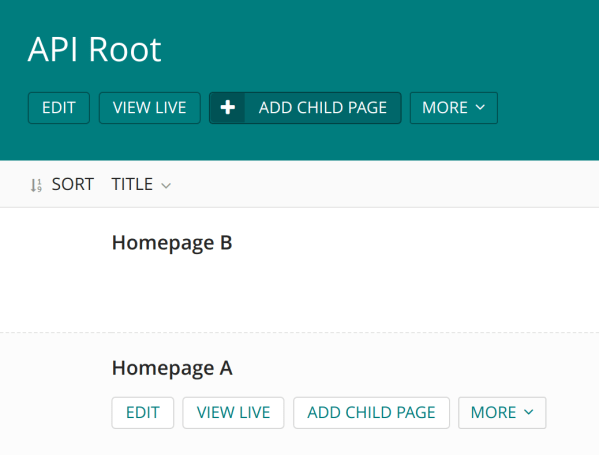

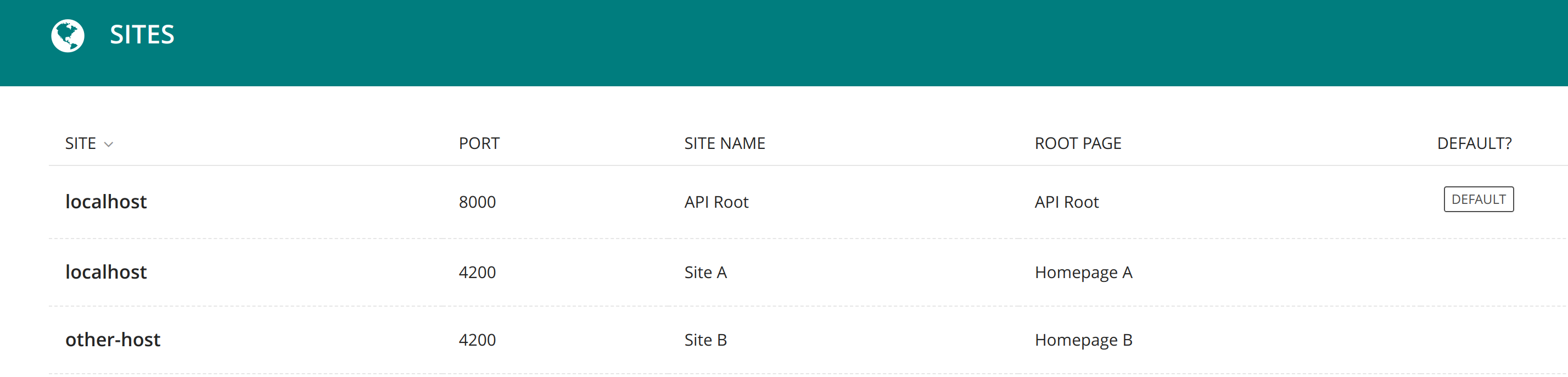

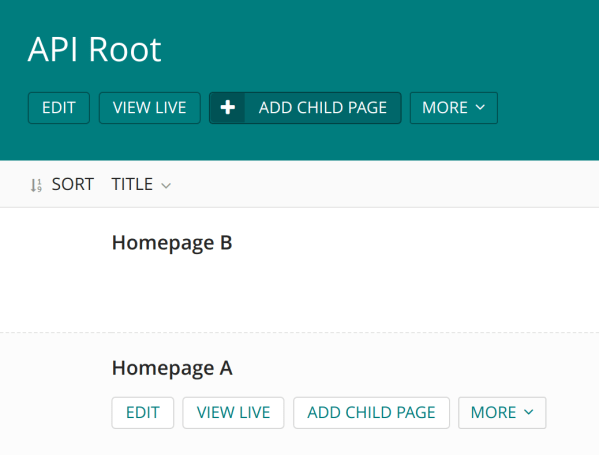

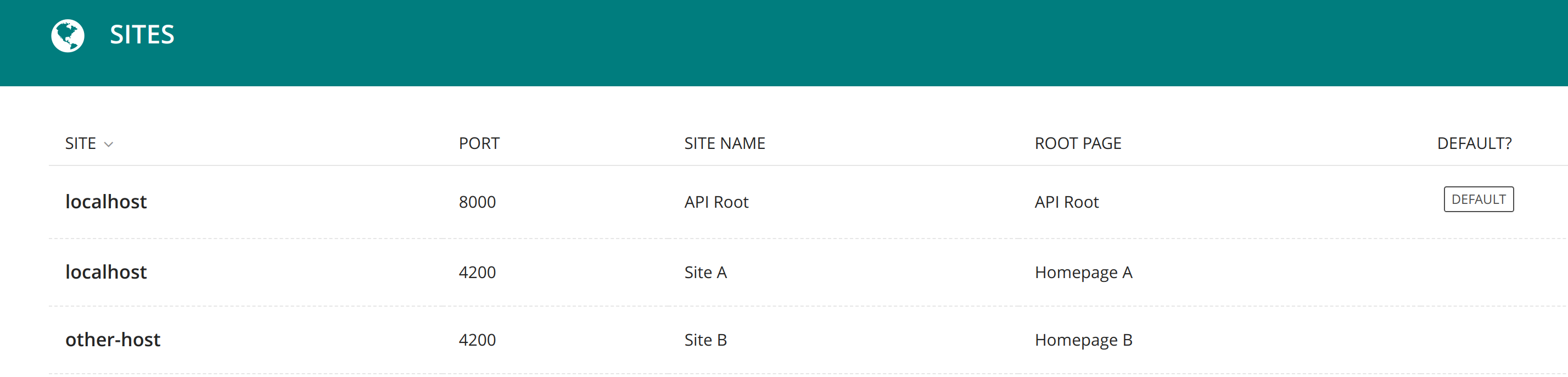

You may want to rename the “Welcome to Wagtail” default page to “API Root” just for clarity. Then create two child pages of any type to act as homepages. If you don’t need multi-site support, just add one instead. Wagtail requires the Sites app to be enabled even if only one site is present. The API Root will still be important later on for distinguishing the Django API server from the front-end Node server.

Next head over to Settings, Sites. Keep the default Site attached to the API Root page. Add another Site for each homepage. If you intend to have two websites, you should have three Wagtail Sites (API Root, Site A, Site B). Each hostname + port combination must be unique. For local development, it doesn’t matter much. For production you may have something like api.example.com, http://www.example.com, and intranet.example.com.

Next let’s set up the Wagtail API. This is already done for you in the sandbox project but when integrating your own app, you may follow the docs here. Then follow Wagtail SPA Integration docs to set up the extended Pages API. Make sure to set WAGTAILAPI_BASE_URL to localhost:8000 if you want to run the site locally on port 8000. Here’s an example of setting up routes.

api.py

from wagtail.api.v2.router import WagtailAPIRouter

from wagtail_spa_integration.views import SPAExtendedPagesAPIEndpoint

api_router = WagtailAPIRouter('wagtailapi')

api_router.register_endpoint('pages', SPAExtendedPagesAPIEndpoint)

urls.py

from django.conf.urls import include, url

from wagtail.core import urls as wagtail_urls

from wagtail_spa_integration.views import RedirectViewSet

from rest_framework.routers import DefaultRouter

from .api import api_router

router = DefaultRouter()

router.register(r'redirects', RedirectViewSet, basename='redirects')

urlpatterns = [

url(r'^api/v2/', api_router.urls),

Test this out by going to localhost:8000/api/ and localhost:8000/api/v2/pages/

If you’d like to enable the Wagtail draft feature – set PREVIEW_DRAFT_CODE in settings.py to any random string. Note this feature will generate special one time, expiring links that do not require authentication to view drafts. This is great for sharing and the codes expire in one day. However if your drafts contain more sensitive data, you may want to add authentication to the Pages API. This is out of scope for Wagtail SPA Integration, but consider using any standard Django Rest Framework authentication such as tokens or JWT. You may want to check if a draft code is present and only check authentication then, so that the normal pages API is public.

Angular Front-end

Now let’s add a new Angular app (or modify an existing one).

- ng new angular-wagtail-demo

- cd angular-wagtail-demo

- npm i angular-wagtail –save

In app.module.ts add

import { WagtailModule } from 'angular-wagtail';

WagtailModule.forRoot({

pageTypes: [],

wagtailSiteDomain: 'http://localhost:8000',

wagtailSiteId: 2,

}),

In app-routing.module.ts add

import { CMSLoaderGuard, CMSLoaderComponent } from 'angular-wagtail';

const routes: Routes = [{ path: '**', component: CMSLoaderComponent, canActivate: [CMSLoaderGuard] }];

This is the minimal configuration. Notice the domain and site ID are set explicitly. This is not required as Wagtail can determine the appropriate site based on domain. However, it’s much easier to set it explicitly so that we don’t have to set up multiple hostnames for local development. Next let’s add a lazy loaded homepage module. Making even the homepage lazy loaded will get us in the habit of making everything a lazy loaded module which improves performance for users who might not visit the homepage first (Such as an ad or search result to a specific page).

ng generate module home --routing

ng generate component home

In app.module.ts add a “page type”. An Angular Wagtail page type is a link between Wagtail Page Types and Angular components. If we make a Wagtail page type “cms_django_app.HomePage” we can link it to an Angular component “HomeComponent”. Page types closely follow the Angular Router, so any router features like resolvers will just work with exactly the same syntax. In fact, angular-wagtail uses the Angular router behind the scenes.

pageTypes: [

{

type: 'sandbox.BarPage',

loadChildren: () => import('./home/home.module').then(m => m.HomeModule)

},

]

This maps sandbox.BarPage from the wagtail-spa-integration sandbox to the HomeModule. “sandbox” is the django app name while BarPage is the model name. This is the same syntax as seen in the Wagtail Pages API and many other places in django to refer to a model (app_label.model). “loadChildren” is the same syntax as the Angular Router. I could set the component instead of loadChildren if I didn’t want lazy loading.

Next edit home/home-routing.module.ts. Since our homepage has only one component, set it to always load that component

home-routing.module.ts with WagtailModule.forFeature

const routes: Routes = [{

path: '',

component: HomeComponent

}];

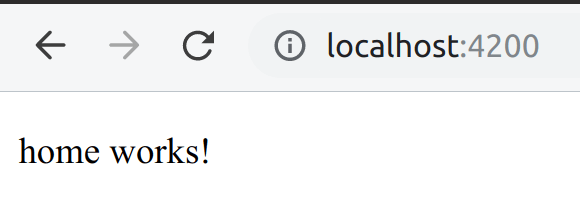

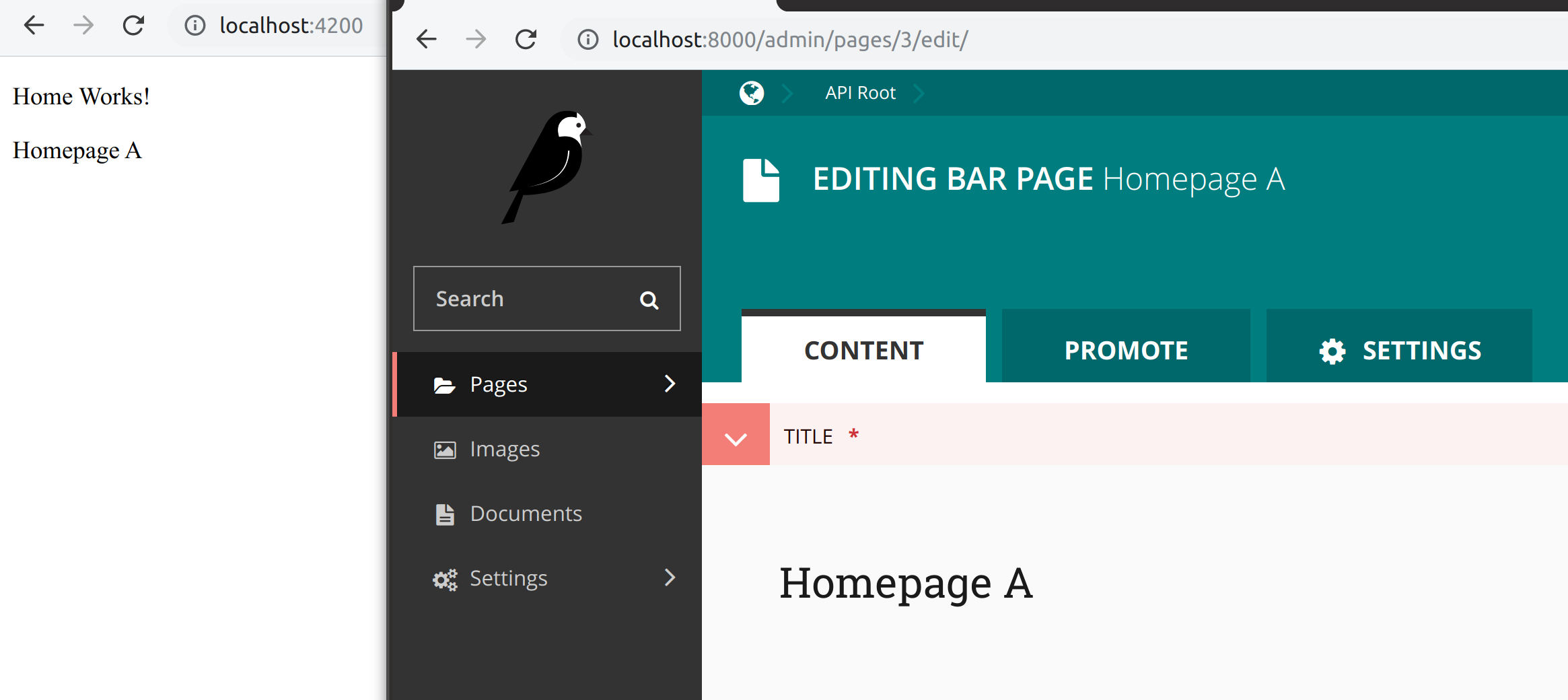

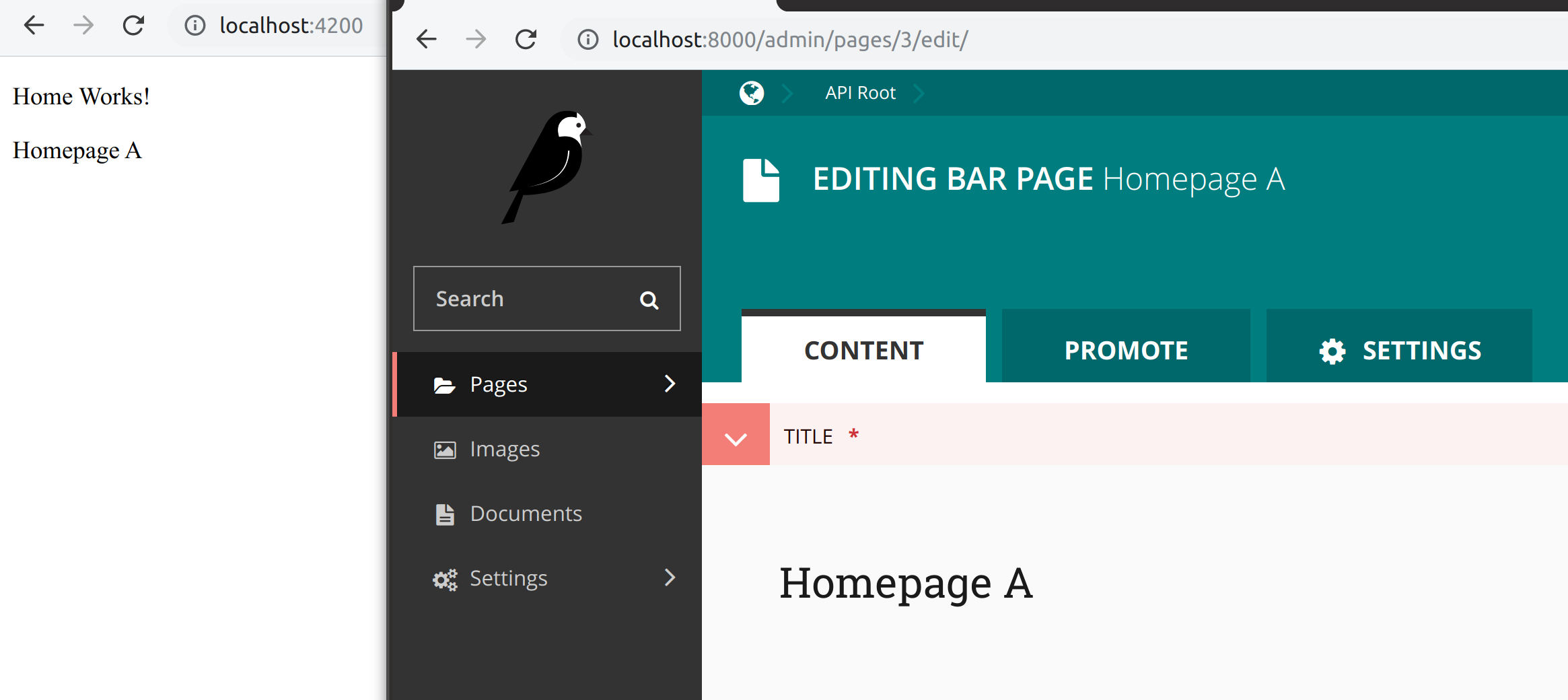

To test everything is working run ”npm start” and go to localhost:4200.

We now have a home page! However, it doesn’t contain any actual CMS data. Let’s start by adding the page’s title. We could get this data on ngOnInit however this would load the data asynchronously after the route is loaded. This can lead to jank because any static content would load immediately on route completion but async data would pop in later. To fix this, we’ll use a resolver. Resolvers can get async data before the route completes.

Edit home-routing.module.ts

import { GetPageDataResolverService } from 'angular-wagtail';

const routes: Routes = [{

path: '',

component: HomeComponent,

resolve: { cmsData: GetPageDataResolverService }

}];

This resolver service will assign an Observable with the CMS data for use in the component. We can use it in our component:

home.component.ts

import { ActivatedRoute } from '@angular/router';

import { Observable } from 'rxjs';

import { map } from 'rxjs/operators';

import { IWagtailPageDetail } from 'angular-wagtail';

interface IHomeDetails extends IWagtailPageDetail {

extra_field: string;

}

@Component({

selector: 'app-home',

template: `

<p>Home Works!</p>

<p>{{ (cmsData$ | async).title }}</p>

`,

})

export class HomeComponent implements OnInit {

public cmsData$: Observable<IHomeDetails>;

constructor(private route: ActivatedRoute) { }

ngOnInit() {

this.cmsData$ = this.route.data.pipe(map(dat => dat.cmsData));

}

}

Going top to bottom, notice how IHomeDetails extends IWagtailPageDetail and adds page specific fields. This should mimic the fields you added when defining the Wagtail Page model. Default Wagtail fields like “title” are included in IWagtailPageDetail.

The template references the variable cmsData$ which is an Observable with all page data as given by the Wagtail Pages API detail view.

ngOnInit is where we set this variable, using route.data. Notice how cmsData is available from the resolver service. When you load the page, you should notice “Home Works!” and the title you set in the CMS load at the same time. Nothing “pops in” which can look bad.

At this point, you have learned the basics of using Angular Wagtail!

Adding a lazy loaded module with multiple routes

Sometimes it’s preferable to have one module with multiple components. For example, there may be 5 components and two of them represent route-able pages. Keeping them grouped in a module increases code readability and makes sense to lazy load the components together. To enable this, make use of WagtailModule.forFeature. Let’s try making a “FooModule” example to demonstrate.

ng generate module foo

ng generate component foo

Edit foo.module.ts

import { NgModule, ComponentFactoryResolver } from '@angular/core';

import { CommonModule } from '@angular/common';

import { WagtailModule, CoalescingComponentFactoryResolver } from 'angular-wagtail';

import { FooComponent } from './foo.component';

@NgModule({

declarations: [FooComponent],

entryComponents: [FooComponent],

imports: [

CommonModule,

WagtailModule.forFeature([

{

type: 'sandbox.FooPage',

component: FooComponent

}

])

]

})

export class FooModule {

constructor(

coalescingResolver: CoalescingComponentFactoryResolver,

localResolver: ComponentFactoryResolver

) {

coalescingResolver.registerResolver(localResolver);

}

}

FooComponent is added to both declarations and entryComponents as it’s not directly added to the router. WagtailModule.forFeature will link the wagtail page type with a component. You can also add a resolver here if needed. Lastly, the constructor adds coalescingResolver. This enabled dynamic component routing between modules and likely won’t be needed in Angular 9 with Ivy and future versions of Angular Wagtail.

Add as many types of page types as desired.

Angular Universal

Angular Universal can generate pages in Node (or prerender them). This is nice for SEO and general performance. The effect is to generate a minimalist static view of the page that runs without JS enabled. Later the JS bundle is loaded and any dynamic content (shopping carts, user account info) is loaded in. Because the server side rendered static page is always the same for all users, it works great with a CDN. I’ve found even complex pages will be around 50kb of data for the first dom paint. Installation is easy.

ng add @nguniversal/express-engine --clientProject angular.io-example

Compile with npm run build:ssrand serve with npm run serve:ssr. Angular Wagtail supports a few environment variables we can set in node. Setting the API server domain and site per deployment is possible:

export WAGTAIL_SITE_ID=2

export CMS_DOMAIN=http://localhost:8000

Confirm it’s working by disabling JavaScript in your browser.

Angular Wagtail provides a few extras for Angular Universal when run in Node (serve:ssr). You can return 404, 302, and 301 status codes by editing server.ts as documented. You can also add the wagtail generated sitemap. Not directly related to Wagtail, but I found helmet and adding a robots.txt pretty helpful too. Angular Univeral just runs express, so anything possible in express is possible in Angular Universal.

Bells and whistles – not found and more SEO

For a real site, consider adding a 404 not found component, setting page meta tags and canonical url. Edit the WagtailModule.forRoot configuration to modify this however you wish. If you followed the server set up from above then Wagtail redirects and drafts should “just work”. Any time Angular Wagtail can’t match a url path to component, it will query the Wagtail SPA Integration redirects API and will redirect if it finds one. If not, Angular Wagtail will show the 404 not found component to the user.

You can find the full angular wagtail demo source on gitlab.